The Real Face of Thomas Jefferson

Life Mask Reconstruction

What did Thomas Jefferson Look Like?

Think you know what Thomas Jefferson really looked like?We can actually know quite a lot—at least about his true facial structure and features.

In 1825, artist John Henri Isaac Browere cast Jefferson’s likeness in plaster, creating a life mask directly from the former president’s face. Browere also made a mask of Jefferson’s close friend James Madison.

Thanks to the lightness of Browere's plaster mixture, the faces were not distorted and were considered highly accurate likenesses.

The substance which Browere applied to his sitter's face was his own invention. Earlier sculptors had used plaster of Paris but that is heavy material and can distort the shape of the face. Browere experimented with different mixtures of plaster until he finally produced a light weight substance. The exact composition of the medium was a closely-guarded secret which Browere passed along only to his son Albertus and which Albertus transmitted to no one."

Jefferson endorsed his life mask bust, as did James and Dolley Madison when they saw it several days later. Madison even wrote:

“Per request of Mr. Browere, busts of myself and of my wife, regarded as exact likenesses, have been executed by him in plaister, being casts made from the moulds formed on our persons, of which this certificate is given under my hand at Montpelier, 19 October, 1825.”

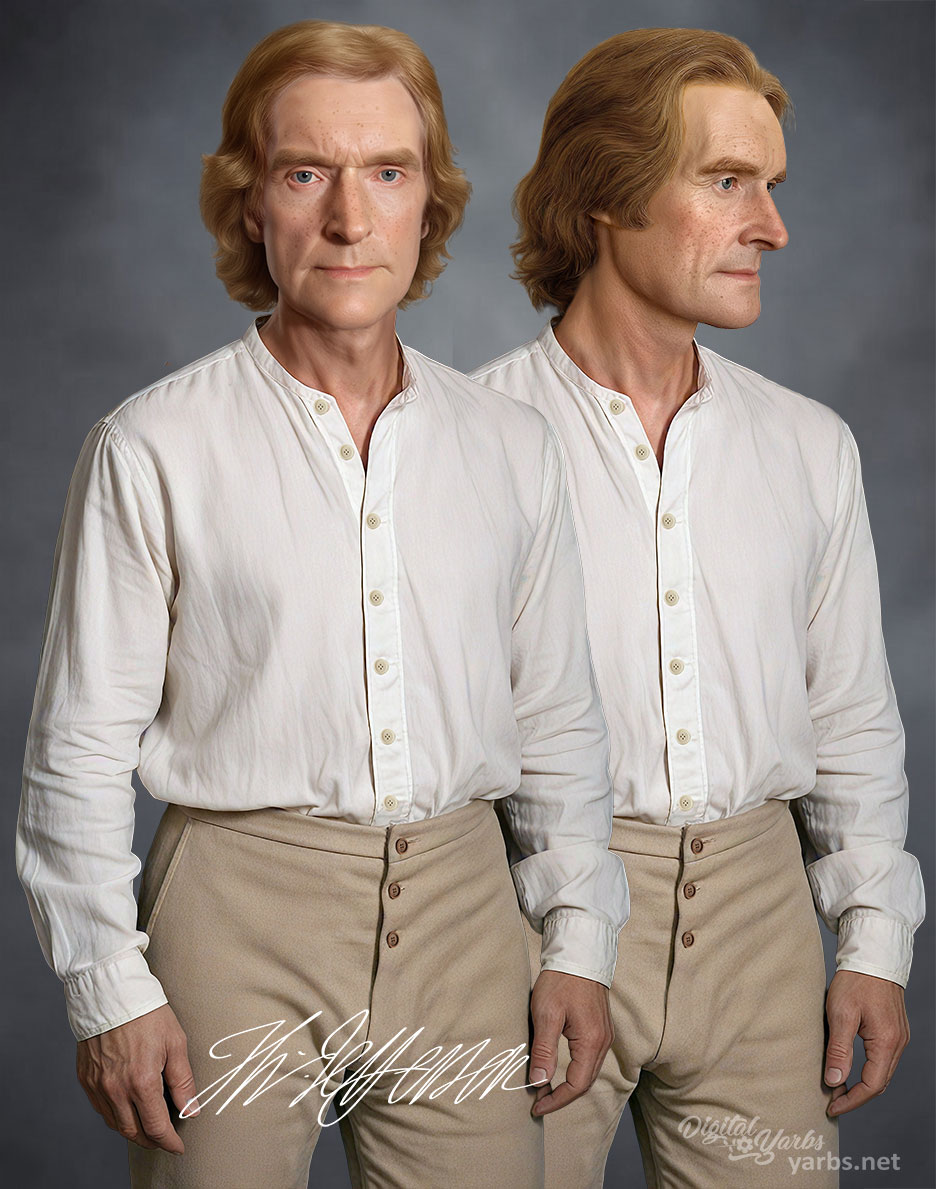

Using Photoshop and AI tools, I’ve reconstructed Jefferson’s appearance from Browere’s original life mask—restoring his natural red hair and showing him as he might have looked in midlife, with a little de-aging since the original mask was taken when Jefferson was in his 80s.

There seems to be no consensus on Jefferson’s eye color. His eyes were variously described by family, friends, and others as blue, gray, “light,” hazel, or combinations thereof. When at home, Jefferson preferred casual, comfortable clothing, so I’ve portrayed him as he might have appeared in a relaxed setting rather than in the formal attire seen in most portraits.

The life mask also reveals details rarely visible in paintings—such as Jefferson’s neck and Adam’s apple. Remarkably, Jefferson aged well, showing fewer wrinkles than Madison, whose life mask displays deep facial lines. Jefferson also retained all his teeth and was known to have freckles. I’ve worked carefully to remain true to the mask’s structure when adding brows, eyes, and lips, to show Jefferson as he truly was.

These are not AI “pump and dump” images. Each was crafted by hand in Photoshop, using AI tools only to assist in historical reconstruction. I hope you enjoy them.

The Browere life masks (in bronze form) are displayed at the Fenimore Art Museum in Cooperstown, New York. The Fenimore graciously allowed me to photograph the original plaster masks, which are normally kept in storage and not open to the public. A heartfelt thank you to the museum for that privilege!

Content creators: You’re welcome to use my images in videos, posts, or blogs for non-commercial purposes—just please credit me for the work.

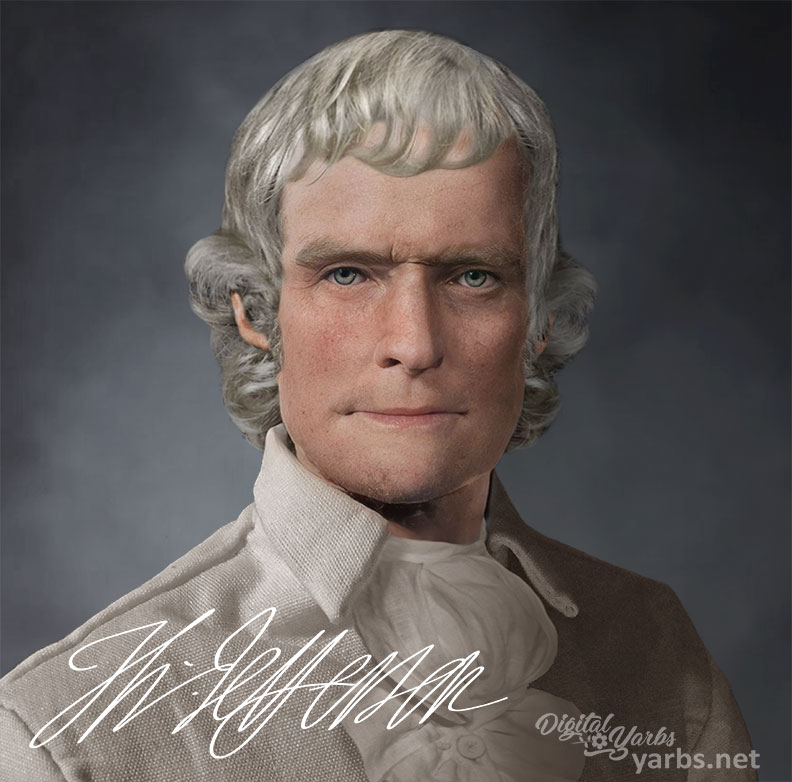

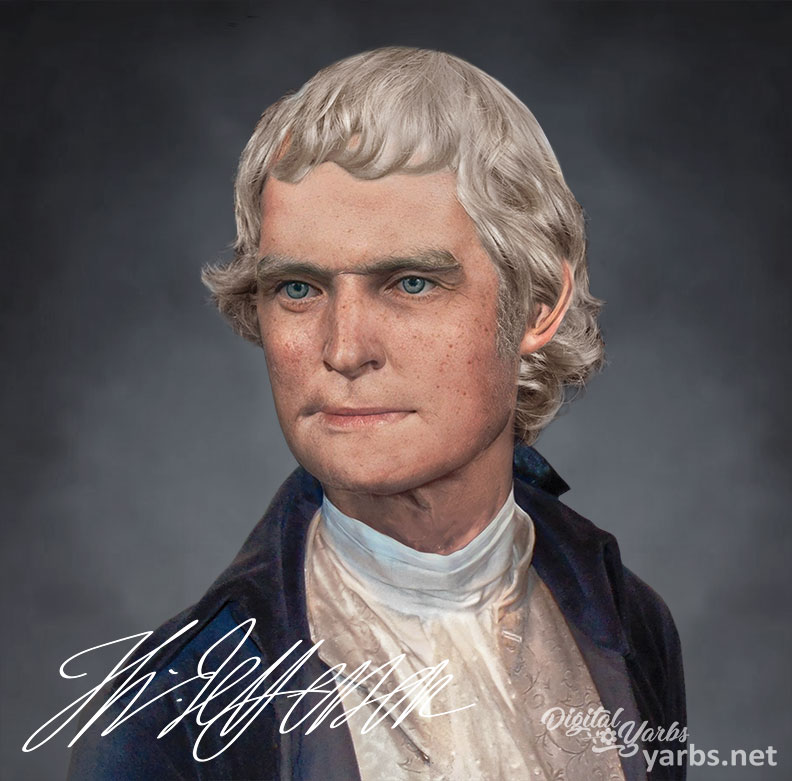

Older Thomas Jefferson Life Mask Recontructions

Here are some earlier Photoshop-only reconstructions of the same Jefferson life mask, depicting him with gray hair. The original photos of the masks weren’t of the highest quality, but they were the best available to work with at the time.

Digital Yarbs Complete Works

Life Mask Facial Reconstructions of History

Witness the authentic faces of historical figures reconstructed with the remarkable capabilities of Photoshop, utilizing actual plaster life mask castings of their heads and upper torsos.

Lost Photographs of History

A captivating collection featuring daguerreotypes, color photographs, and artwork inspired by meticulously reconstructed life masks of prominent figures from American history, including the founding fathers.

Colorizations and Enhancements

Utilizing the powerful tools of Adobe Photoshop and AI, I breathe new life into vintage photographs and daguerreotypes by colorizing, enhancing, de-aging, and occasionally reconstructing them.

Free Image Downloads

Tired of AI-generated historical figures that don’t actually resemble the real people? Free historically accurate images for you to use!

Latest Digital Yarbs Video

Click that red subscribe button to stay up to date with my latest content.