Home >> Lost Photographs of History >>John Quincy Adams at Peacefield

Lost Photos of History – John Quincy Adams at Peacefield

He rests with the immortals; his journey has been long:

For him no wail of sorrow, but a paean full and strong!

So well and bravely has he done the work be found to do,

To justice, freedom, duty, God, and man forever true.

—Whittier.1

“Historians generally agree that the single figure bridging America’s creation and near-dissolution is John Quincy Adams (1767-1848), who before his eighth birthday heard cannon fire from Bunker Hill and, seven decades later, as the only former President to serve in the House of Representatives, suffered a fatal stroke in the presence of Congressman Abraham Lincoln.”2

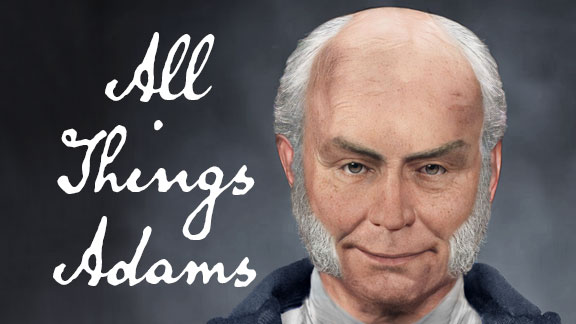

Old Man Eloquent Himself

After a most enjoyable visit with Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, our time-travel adventure led us to Quincy, Massachusetts. Here we got to meet “Old Man Eloquent” himself, former 6th President of United States, John Quincy Adams.

We entered his home, called Peacefield, which also once served as the residence of his father, 2nd President John Adams. In the front entrance beside the stairway, I snapped this photo of Adams. He was well dressed and in his top hat, ready to leave when we arrived. Adams, who was familiar with photography, a medium in its infancy, was quite taken by a “digital” camera and almost speechless when introduced to a cell phone. What! Old Man Eloquent at a loss for words? It cannot be so.

John Quincy Adams at his Peacefield home in Quincy, MA. Image made from the 1825 life mask casting of Adam’s head and upper torso by J. I. Browere. Period dress body: Vincent Puliafico, Background image: Google

Here I was shaking the hands of a man with an IQ estimated at 175 who could speak and read seven languages. He was a Bible believer, as well as a leading force for the promotion of science. He helped start the process and was a supporter for a national observatory and the Smithsonian Institution.3

Mr. Adams is an enigma. A man of genius intelligence who embraces a belief in the Bible and science, something the people of our time would deem as mutually exclusive.

I told Mr. Adams how one of my southern friends asked me how I could possibly like John Quincy Adams, that old “New England Yankee”. Mr. Adams quickly informed me that southerners would forever remember him as “the acutest, the astutest, the archest enemy of southern slavery that ever existed.4

Mr. Adams also informed me that he was apposed to Texas statehood. I asked why.

“Because it would mean another abominable slave state in the Union and in congress. A slaveholder’s plot,” he said.5

I informed Mr. Adams that relations between the states had gone “south” so to speak after his time and that we had a civil war. He was quick to let me know that he had predicted such.6

Unfortunately, we could not spend as much time with Mr. Adams as we had wanted, but he promised us we could have a tour of his home on our next visit.

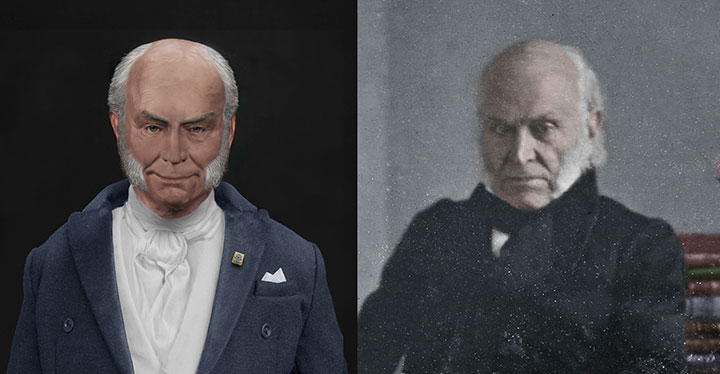

Closer view of John Quincy Adams at his Peacefield home in Quincy, MA. Image made from the 1825 life mask casting of Adam’s head and upper torso by J. I. Browere. Period dress body: Vincent Puliafico, Background image: Google

A Death Blow to the Slave Power

“The lot of ex-Presidents of the United States, as a rule, has been a life of extreme retirement, but to this rule there is one marked exception. When John Quincy Adams left the White House in March, 1829, it must have seemed as if public life could hold nothing more for him. He had had everything apparently that an American statesman could hope for. He had been Minister to Holland and Prussia, to Russia and England. He had been a Senator of the United States, Secretary of State for eight years, and finally President. Yet, notwithstanding all this, the greatest part of his career, and his noblest service to his country, were still before him when he gave up the Presidency.”7

“In the following year (1830) he was told that he might be elected to the House of Representatives, and the gentleman who made the proposition ventured to say that he thought an ex-President, by taking such a position, “instead of degrading the individual would elevate the representative character.” Mr. Adams replied that he had “in that respect no scruples whatever. No person can be degraded by serving the people as Representative in Congress, nor, in my opinion, would an ex-President of the United States be degraded by serving as a selectman of his town if elected thereto by the people.” A few weeks later he was chosen to the House, and the district continued to send him every two years from that time until his death. He did much excellent work in the House, and was conspicuous in more than one memorable scene; but here it is possible to touch on only a single point, where he came forward as the champion of a great principle, and fought a battle for the right which will always be remembered among the great deeds of American public men.”8

Sepia toned close-up image of John Quincy Adams at his Peacefield home in Quincy, MA. Image made from the 1825 life mask casting of Adam’s head and upper torso by J. I. Browere. Period dress body: Vincent Puliafico, Background image: Google

“Soon after Mr. Adams took his seat in Congress, the movement for the abolition of slavery was begun by a few obscure agitators. It did not at first attract much attention, but as it went on it gradually exasperated the overbearing temper of the Southern slaveholders. One fruit of this agitation was the appearance of petitions for the abolition of slavery in the House of Representatives. A few were presented by Mr. Adams without attracting much notice; but as the petitions multiplied, the Southern representatives became aroused. They assailed Mr. Adams for presenting them, and finally passed what was known as the gag rule, which prevented the reception of these petitions by the House. Against this rule Mr. Adams protested, in the midst of the loud shouts of the Southerners, as a violation of his constitutional rights. But the tyranny of slavery at that time was so complete that the rule was adopted and enforced, and the slaveholders, undertook in this way to suppress free speech in the House, just as they also undertook to prevent the transmission through the mails of any writings adverse to slavery.”9

Close-up image of John Quincy Adams at his Peacefield home in Quincy, MA. Image made from the 1825 life mask casting of Adam’s head and upper torso by J. I. Browere. Period dress body: Vincent Puliafico, Background image: Google

“With the wisdom of a statesman and a man of affairs, Mr. Adams addressed himself to the one practical point of the contest. He did not enter upon a discussion of slavery or of its abolition, but turned his whole force toward the vindication of the right of petition. On every petition day he would offer, in constantly increasing numbers, petitions which came to him from all parts of the country for the abolition of slavery, in this way driving the Southern representatives almost to madness, despite their rule which prevented the reception of such documents when offered. Their hatred of Mr. Adams is something difficult to conceive, and they were burning to break him down, and, if possible, drive him from the House. On February 6, 1837, after presenting the usual petitions, Mr. Adams offered one upon which he said he should like the judgment of the Speaker as to its propriety, inasmuch as it was a petition from slaves. In a moment the House was in a tumult, and loud cries of “Expel him!” “Expel him!” rose in all directions. One resolution after another was offered looking toward his expulsion or censure, and it was not until February 9, three days later, that he was able to take the floor in his own defense. His speech was a masterpiece of argument, invective, and sarcasm. He showed, among other things, that he had not offered the petition, but had only asked the opinion of the Speaker upon it, and that the petition itself prayed that slavery should not be abolished. When he closed his speech, which was quite as savage as any made against him, and infinitely abler, no one desired to reply, and the idea of censuring him was dropped.”10

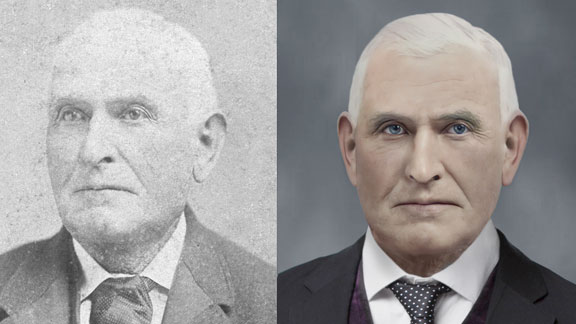

Below is the original daguerreotype used for the composition.

Left: Photoshop reconstruction of the 1825 life mask of John Quincy Adams by J. I. Browere, Right: 1843 colorized photograph of John Quincy Adams by Phillip Haas

“The greatest struggle, however, came five years later, when, on January 21, 1842, Mr. Adams presented the petition of certain citizens of Haverhill, Massachusetts, praying for the dissolution of the Union on account of slavery. His enemies felt that now, at last, he had delivered himself into their hands. Again arose the cry for his expulsion, and again vituperation was poured out upon him, and resolutions to expel him freely introduced. When he got the floor to speak in his own defense, he faced an excited House, almost unanimously hostile to him, and possessing, as he well knew, both the will and the power to drive him from its walls. But there was no wavering in Mr. Adams. “If they say they will try me,” he said, “they must try me. If they say they will punish me, they must punish me. But if they say that in peace and mercy they will spare me expulsion, I disdain and cast away their mercy, and I ask if they will come to such a trial and expel me. I defy them. I have constituents to go to, and they will have something to say if this House expels me, nor will it be long before the gentlemen will see me here again.” The fight went on for nearly a fortnight, and on February 7 the whole subject was finally laid on the table. The sturdy, dogged fighter, single-handed and alone, had beaten all the forces of the South and of slavery. No more memorable fight has ever been made by one man in a parliamentary body, and after this decisive struggle the tide began to turn. Every year Mr. Adams renewed his motion to strike out the gag rule, and forced it to a vote. Gradually the majority against it dwindled, until at last, on December 3, 1844, his motion prevailed. Freedom of speech had been vindicated in the American House of Representatives, the right of petition had been won, and the first great blow against the slave power had been struck.”11

Special thanks to Vincent Puliafico for image usage.

Sources & References:

1,7,8,9,10,11Henry Cabot Lodge, and Theodore Roosevelt. “Hero Tales From American History” 1895 October 10, 2008 [EBook #1864] https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1864/1864-h/1864-h.htm#link2H_4_0014 (Public Domain)

2Thomas Mallon. “Born To Do It. New biographies of John Quincy Adams and his wife.” The New Yorker. May 14, 2014 https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2014/05/05/born-to-do-it

3Tacky Spoons. “Day 192 – The John Quincy Adams Spoon” http://www.tackyspoons.com/2017/07/day-192-the-john-quincy-adams-spoon/

4,6Wikipedia. “John Quincy Adams and abolitionism” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Quincy_Adams_and_abolitionism